A comparative study of Juraj Herz’s The Virgin and the Monster and its literary sources

“Je suis votre miroir, la Belle.

Réfléchissez pour moi.

Je réfléchirai pour vous.”

“I am your mirror, Beauty.

Reflect for me.

I will reflect for you.”Jean Cocteau, La Belle et la Bête (1970, 134-35)

A thick, grey fog drifting through a leafless, dark forest.

A caravan of horse-drawn carts, accompanied by panting men, their faces joyless and filthy. They try to find their way over rain-soaked, muddy paths.

Then the band’s sole woman ominously proclaims: “We should not cross these evil roots.”

A shot of cawing crows circling the unlucky ones in the sky above their heads.

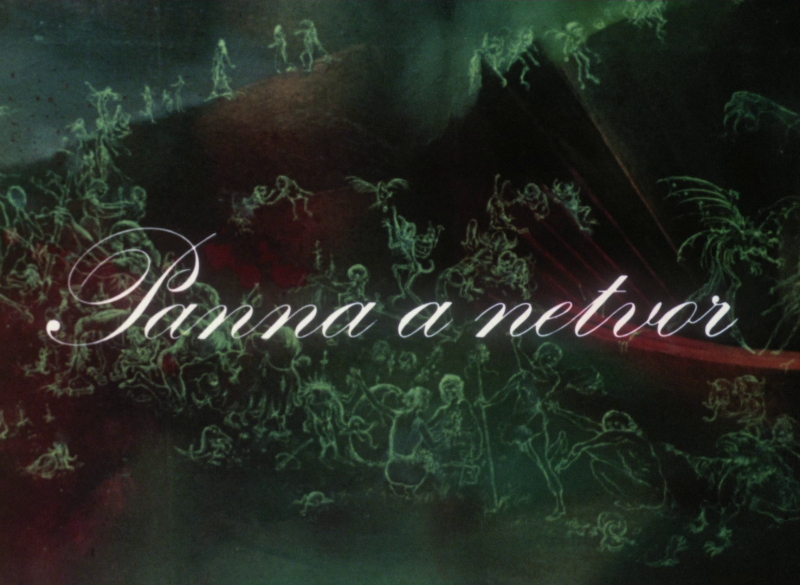

This is how Juraj Herz’s 1978 The Virgin and the Monster (Panna a Netvor), a Czechoslovakian adaptation of the famous Beauty and the Beast tale, begins. Following this opening sequence, the titles, accompanied by Petr Hapka’s organ music, show artist Josef Vylet’al’s paintings of Boschian figures in several states of pain and discomfort (fig. 1). When the next scene graphically shows villagers slaying and gutting some farm animals, we know we are far removed from singing pendulums and teapots and have undoubtedly entered the realm of horror.

This essay will explore the relation of The Virgin and the Monster to its source texts: Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve’s original novel and its highly abridged and more widely known adaptation by Marie le Prince de Beaumont. It will argue that Herz’s film should be considered more on neo-Freudian terms, rather than eighteenth-century moral terms. Furthermore, the film will be discussed as an extended dream, delusion, or even an after-death scenario.

A point-to-point analysis of which narrative or thematic features are present or absent in all versions will be beside the point and, because of the scope of the works (De Villeneuve’s version runs for some two-hundred pages), near-impossible and unnecessary to provide. So instead, we will list some evident and unavoidable differences between the versions and examine the possible reasons for these alterations.

According to many, the origin of the Beauty and the Beast tale type can be found in Apuleius’ story of Cupid (or Amor) and Psyche for his Metamorphosis (2nd century AD). The story’s overarching theme – an animal as bridegroom – can be found as tale type 425 in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index. The most-known variant today, more commonly known as (The) Beauty and the Beast (after Villeneuve), gets its own subsection: 425C. While the origin of the Beauty and the Beast story can incontestably be found in Villeneuve’s novel, the genesis of the general tale type 425 is not as clear-cut. While Apuleius may indeed have been the first to write down the story, its origins could very well go back even further. The monumental Enzyklopädie des Märchens mentions that the tale might have its origins as far back as the Mycenean age, “an epoch where, as is generally assumed, the ancient Greek myths have their origin” (Megas 1977, 472). According to Ruth B. Bottigheimer, after time Apuleius’ tale all but lost its place in literary and public consciousness, until it

re-emerged in MS [manuscript] in the late Middle Ages and – of greater consequence – was printed in 1469 in an edition whose Latin text eventually spread throughout Europe … Subsequently translated out of Latin for larger reading publics with less education, Apuleius’ text took on local coloration from the vernacular culture surrounding each new language in which it appeared. From this process emerged a family of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ tales, whose plots arise from a narrative … [in which] a beautiful woman accept[s] and love[s] an ugly husband. (2015, 53)

Under its title La Belle et la Bête, the version most commonly known today was originally written by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve for inclusion in her book La Jeune Amériquaine et les Contes Marins (1740) and was later severely abridged and slightly changed to make it accessible for (bourgeois) children by Marie le Prince de Beaumont. It was included in De Beaumont’s didactic and moralistic four-part Magasin des Enfants (1756-57) (Rietveld-Van Wingerden 2004, 11).

Before discussing the filmic adaptations of the story, a summary of De Villeneuve’s source novel is in order:

A wealthy merchant lives with his six sons and six daughters, one of whom is simply called ‘the Beauty,’ when he loses his wealth because of misfortune: his ships with trading goods are lost at sea. Moneylenders threaten to take away the family’s remaining wealth, when the father hears of one of his ships having made it to shore. Setting out to recover his lost goods, the merchant asks his daughters if they desire any gifts from the city. While his other daughters demand expensive clothes and jewels, the Beauty asks for only a rose, not wanting to inconvenience her father. The merchant sets out to settle his affairs, only to discover that his debtors have taken all his riches. On his way home, a storm overtakes the merchant, and looking for shelter, he stumbles upon a hidden castle in the woods, where magically, food and a fire are laid out for him. Having spent a night in the castle, the merchant prepares to leave for home when he encounters a rosebush. Remembering the Beauty’s wish for a rose, he plucks the flower. A beast appears and scolds the man for picking his flower. He wants to kill the man for his “ingratitude,” but proposes that instead of killing him, the merchant may send one of his daughters to the castle to live with the Beast in perpetuity. The merchant is allowed to go home and relates the story to his family. The Beauty feels prompted to offer herself to the Beast, and together she and her father return to the Beast’s castle. Her father leaves, and the Beauty is left in the castle – alone with the Beast and several magical animals. The Beast has provided a magical room where the windows look out on all leading theatre stages for amusement. At night, the Beauty dreams of a handsome young man, whose portrait can be found all around the castle. Every night, the Beast asks the Beauty if she will marry him, but she refuses him every time. Wanting to be with her family one more time, the Beast allows the Beauty to go home for two months, after which time she is expected to turn a ring on her finger to return to the castle forever. However, the Beauty, through the scheming of her jealous sisters, exceeds this time. Feeling remorse, the Beauty eventually returns to the Beast, who is dying. The Beauty realizes she loves the Beast and telling him so, the Beast transforms into the prince from her dreams.

While most adaptations of the story end here, De Villeneuve’s original contains a second part, where the reason behind the enchantment is revealed. Since this second part is mostly absent from later adaptations, we will not outline this part extensively. Coarsely summarized, it turns out that the Beauty was an unknowing instrument in a family feud by the Queen and her fairy sisters. An evil fairy, in love with the prince, puts a spell on him and his castle out of spite of being refused by him. Only through a voluntary profession of love by an unblemished maiden could the spell on the Beast be broken. In the end, the Beauty, hesitant to marry above her standing, turns out to be the beast/prince’s niece, placed in her foster home as a baby by the evil fairy’s sister. The Beauty and the prince marry, and, in the end, her foster family is allowed to work at their court in the castle.

De Beaumont’s version, written sixteen years after the original, greatly condenses the tale while retaining the general plot of De Villeneuve’s story. She (arbitrarily) reduces the merchant’s siblings to six instead of twelve, and there is no dreaming of a prince in her version. The business with the monarchs and the fairies is reduced to one subsentence, and the Beauty no longer is the prince’s niece. However, the most striking difference with De Villeneuve’s original is the moralistic ending De Beaumont tacks on. The disagreeable sisters are punished for their jealousy and are enchanted into two stone door pillars to stand forever in front of the castle and deliberate their sins in perpetuity.

It is essential to remember the era in which De Villeneuve and De Beaumont wrote their versions of the Beauty and the Beast tale, as well as its target audience. While the general tale type might indeed be one of the “most beautiful and widespread fairy tales of the Indo-European world” (Megas 1977, 472), De Villeneuve’s variant is unmistakably of her time. The writer is the first “fairy tale writer to take the figure of a monster bridegroom and set her Beauty and the Beast amid aristocratic wealth, sophistication and corruption resembling her own contemporaries’ circumstances – her fairies are thinly disguised courtiers and social operators” (Warner 2018, 9). A bourgeois woman’s defining traits in De Villeneuve’s era are selflessness and faithfulness. This is reflected in ‘the Beauty’ remaining nameless throughout the tale. She is only signified by her ‘virtue’ of beauty. According to fairy tale scholar Jack Zipes, these were “topic[s] of interest to women at that time, for they were beginning to rebel against the arranged marriages or marriages of convenience” (2011, 227). Zipes points out that not only is Beauty willing to sacrifice herself to live with the Beast, but she is doubly willing to do so when she, still believing herself to be of lower heritage than her would-be husband, wants to forfeit the marriage to a nobleman.

De Beaumont’s adaptation for children, to be read to them by their governesses, goes a bit further than De Villeneuve’s and transforms the story into a “vehicle for indoctrinating and enlightening children” (Tatar 2016, 33). Not only did De Beaumont “set out to soothe the fears of élite young women about the economic unions planned for them” (Warner 2018, 9), she ingrains the story with the emphatic message that a good and virtuous life for a woman equals a life of docility and denying of the self.

While the original is still widely read today, later versions of the Beauty and the Beast tale moved away from heavy moralizing and didacticism. Maria Tatar emphasizes the tale’s proclivity to keep asking questions about relationships, marriage, and agency (30). Indeed, the Beauty and the Beast tale keeps getting re-told and adapted, and every era gets a version of the tale it suits. Betsy Hearne discerns an inward move towards a deeper psychological understanding in fairy tale adaptations in the first half of the twentieth century:

Not only has the story’s kernel been exposed, but also its characters’ internal conflicts and motivations. The characters speak directly, for themselves, and introspectively, of themselves. The growing prevalence of psychological interpretation during the first half of the twentieth century has affected the story’s recreators, who explicitly explore in art forms the fairy tale motifs which their scientific colleagues analyze. (1991, 79)

Indeed, Hearne’s words make sense considering Juraj Herz’s 1978 filmic adaptation of the work. While heavily indebted to Jean Cocteau’s seminal version, Herz’s version stands on its own as a work steeped in oneiricism, existential duality, and (female) sexuality.

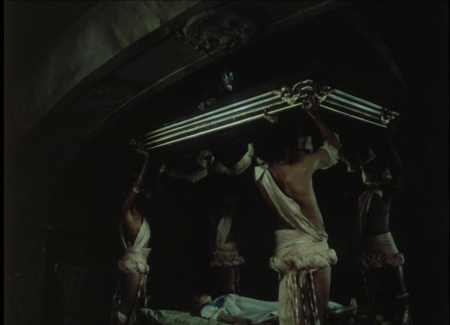

Herz’s version immediately sets itself apart from De Villeneuve and De Beaumont by its nihilistic and horrific opening scene where the merchant’s treasure (now being shipped in carts instead of ships) is hauled through an oppressive forest, only for the carts to be destroyed and the caravan’s members being either burned alive or slashed to death by the Beast. In the following sequence, the villagers, while being fairly anonymous in the source material, are implied to be even more beastly than the Beast – they unflinchingly kill and flay unanesthetized animals and enrich their broth with generous dollops of animal blood. The Beauty in Herz’s version is a young woman setting herself apart from her two (not five) nagging sisters, and this is a rare version where the Beaty gets a name: Julie – tellingly named after the God of light and generally associated with youthfulness (Cinnelli 2021). A portrait of Julie’s mother prominently hangs in her family’s home, establishing in dialogue Julie’s outsider position as a half-sister. One of the most significant differences between Herz and De Villeneuve/De Beaumont arrives in the form of the Beast. While neither De Villeneuve nor De Beaumont describe the Beast apart from the adjective ‘horrible,’ most illustrators, and especially filmmakers (taking their cue from Cocteau) have presented the Beast as a relatively dignified lion-like, or at least mammalian figure. However, Herz presents the Beast as an avian creature with a filthy beak, ragged clothes, and an altogether frightful appearance (fig. 2). In The Virgin and the Monster, the merchant sets out to sell his last valuable: a portrait of Julie’s mother, when he stumbles upon the Beast’s castle. This castle is not, as in the source novel, a place of grandiose splendor, but a dilapidated mansion, overgrown with vines, with sulphurous, bubbling mud pits and crumbling walls open to the forest. After the father relates his story and fatal deal with the monster to his family, Julie, donning a white robe, departs to the Beast’s castle without a moment’s doubt. Here, Julie finds a castle filled with mirrors and grotesquely distorted portraits, amongst which a portrait of the prince in seeming mid-progress of becoming the Beast (fig. 3). Julie is drugged by the Beast and falls asleep on a bed that slowly lowers down to enclose her, coffin-like, with a demon figure sitting on top. After this, the Beast is seen putting his claw on the drugged, sleeping Julie’s throat. Meanwhile, Julie dreams of doors opening and being carried away by a handsome prince. Throughout the film, the Beast is in a constant dialogue with his inner voice telling him to kill Julie or kill himself (a feature taken from playwright Ceský Krumlov). “I don’t need her blood – the wood is full of deer,” the Beast utters, after which he (graphically) kills a deer in the woods (mirroring the opening sequence of the villagers killing animals). Throughout her stay in the castle, the Beast asks Julie not to look at him. They do not dine together, and the Beast does not ask Julie to marry him every night. When Julie tricks the Beast and touches his claws, they metamorphose into human hands. Julie decides to leave the castle and go back home (no proviso to come back here). The Beast, robbed of his claws and thus unable to kill for sustenance, is in psychological and physical torment. He sets part of his castle afire and waits for death to set in. However, Julie returns out of her own accord and professes her love for the monster, after which he transforms into the prince of her dreams. The dream scene, with Julie in the arms of the prince, is repeated, and the film ends. There is no explanation for the Beast’s enchantment, and we never hear of Julie’s family again.

Herz’s film differs significantly from its source in its grotesque and uncanny aesthetic, as well as in the agency of the Beauty and Beast figures. While in De Villeneuve’s, and especially in De Beaumont’s version, the Beauty is a blank canvas on which the prospected (female) reader can project the virtues of the time – self-repudiation chiefly amongst them – Herz’s Julie has far more agency. Here we encounter a young woman with a mind of her own and, being away from home, discovering her own character and sexuality. Herz’s version allows for multiple interpretations of the tale on top of being a ‘traditional’ girl-meets-monster/prince tale. The film can foremost be seen as a parable for Julie’s sexual awakening, or might even be conceived as a (delusional or after-death) dream.

We will briefly discuss the first point by highlighting some additions Herz made to the De Villeneuve/De Beaumont source story. Herz explores the love Julie feels for her father (a rather bland figure in the original) and subtly implies Julie having a possible Elektra Complex. In psychoanalysis this Complex generally occurs in a young woman’s early life stage where she develops her sexuality and wants to possess her father over her mother. The more-than-platonic relation between Julie and her father could be suggested by the scene where Julie leads her father by the hand to the upstairs floor (her bedroom?) in the family home. Moreover, the Beast is repeatedly seen obsessing over the portrait of Julie’s mother – a spitting image of Julie herself. Julie seduces the Beast in veritable competition with her (deceased) mother. Apropos, Jana Marková argues that Julie “gradually exchanges her love for her father for her love of the Monster” (2014, 44). Julie’s sexual awakening and the implied sexual relation between her and the Beast is further enhanced by the many references to blood in the film. After drugging her and (implicitly) about to rape Julie, the Beast says he does not want her (virginal?) blood and kills a young, innocent doe instead. Indeed, Jonathan Owen gives this specific scene as an example of The Virgin and the Monster’s duality between Julie’s erotic fantasies (she dreams about her prince), and the Beast’s instinctual, brutish sexuality (2021, 13). Incidentally, many Beauty and the Beast scholars have emphasized the tale’s theme of (burgeoning) sexuality (Bottigheimer 2015, 55). Herz, influenced by Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête (Owen 2021, 5), inhabits his tale with numerous mirrors and mirror motifs and conceivably takes a page from Lacanian psychoanalytic theory. The Lacanian mirror stage, where a child looking into a mirror sees itself as another, or an Other, for the first time, relates closely to the libidinal stage in infancy: “it has historical value as it marks a decisive turning-point in the mental development of the child [and] typifies an essential libidinal relationship with the body-image … demonstrat[ing] clearly the passing of the individual to a stage where the earliest formation of ego can be observed” (Lacan 1951, 14). The Beauty in De Villeneuve’s and De Beaumont’s versions has not reached this (metaphorical) state yet, but Herz’s Julie, and perhaps even his Beast, have undoubtedly entered this stage of bodily and sexual change. In this respect, the doors opening before the couple in the dream and ending scene are not-so-subtle metaphors for sexual awakening.

Herz lets Julie leave her home in a white garb. Tellingly, white is the color most associated with virginity and innocence. However, the white (bridal?) garb might additionally be conceived as a funereal dress. Julie might as well dream the entire episode after having been drugged and lowered into her casket-like bed. To strengthen this hypothesis, Herz places a demon atop the closing bed, not dissimilar to the folkloristic image of the nightmare (fig. 4). Everything that happens after this scene might therefore be a dream or even an after-death scenario. This idea is strengthened when the assumed “real” last scene mirrors Julie’s earlier dream scene one-on-one. Talking about Cocteau’s earlier film, Deborah Allison considers the possibility of the Beauty passing into death: “Belle undoubtedly traces the footsteps of Persephone and other mythic predecessors who venture into an underworld filled with temptation and danger before an ultimate coupling with its sovereign snaps shut (in Cocteau’s words) ‘the trap in which Belle is to be caught for all eternity’” (2018, 4). According to Miranda Benson, the dream/nightmare hypothesis for the tale in general has been offered (though is now questioned) by many Beauty and the Beast scholars before (1997, 60). Another possibility might be that The Virgin and the Monster’s entire diegesis is the subjective delusion of Julie. The Beast might not even transform into a prince or even be a beast at all. This might account for the Beast suddenly gaining human hands.

In adapting the famous Beauty and the Beast tale, Juraj Herz has created an updated version steeped in psychoanalysis and might have provided more questions than answers. There are many more nuances and intricacies to Herz’s adaptation than space permits us to discuss. The director has taken the source novel and its adaptation and gave it a decidedly adult twist, far removed from De Beaumont’s and De Villeneuve’s morals that form an ill fit with twentieth- and twenty-first-century norms and values. Herz himself was hesitant to shoot another version of the story after Cocteau’s masterpiece but managed to build upon that film’s dreamlike strengths and deepen the story once more. While retaining the general framework of the source tale, Herz incorporated highly distinctive and altogether darker elements that are only transiently present in the French literary originals. Doing so, he created a new work that asks (uncomfortable) questions about death, sexuality, and individuality. “Nearly every culture tells “Beauty and the Beast” in one fashion or another, making the story new so that we think more and think harder,” Maria Tatar wrote (2016, 30). In this light, Panne e Netvor is a valuable new entry into the Beauty and the Beast canon.

Sources

Allison, Deborah. “Cocteau, La Belle et la Bête and the World of Dreams.” In booklet to La Belle et la Bête. British Film Institute, 2018. 1-5.

Bensing, Miranda. “Belle en het Beest.” In Van Aladdin Tot Zwaan Kleef Aan: Lexicon Van Sprookjes: Ontstaan, Ontwikkeling, Variaties, edited by Ton Dekker, Jurjen van der Kooi, and Theo Meder, Antwerpen: Kritak, 1997. 56-61.

Bottigheimer, Ruth B. “Beauty and the Beast.” In The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales: Second Edition, edited by Jack Zipes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. 53-55.

Cinelli, Elisa. “Julia Name Meaning.” Very Well Family. About, Inc., 11 July 2021. www.verywellfamily.com/julia-name-meaning-origin-popularity-5188658

Cocteau, Jean. La Belle et la Bête: Scénario et Dialogues de Jean Cocteau. New York: New York University Press, 1970.

Hearne, Betsy. Beauty and the Beast: Visions and Revisions of an Old Tale. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Herz, Juraj. The Virgin and the Monster / Panna a Netvor. Second Run Ltd., 2021. Blu-ray.

Lacan, Jacques. “Some Reflections of the Ego.” The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis vol. 34, 1951. 11-17.

Le Prince de Beaumont. De Schoone & het Beest. St. Geschiedenis Kinder- en Jeugdliteratuur. 2004.

Marková, Jana. Prvky Hororu a Pohádky Ve Filmové Tvorbě Juraje Herze v Období Normalizace: Elements of Horror and Fairy Tale Genre in Films by Juraj Herz in the Period of Normalization. PhD diss. Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2014.

Megas, Giorgios A. “Amor und Psyche.” In Enzyklopädie des Märchens, edited by Kurth Ranke et al. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1977. 464-472.

Owen, Jonathan. “A Very Different Beast: Juraj Herz’s Beauty and the Beast.” In booklet to The Virgin and the Monster / Panna a Netvor. Second Run Ltd., 2021. 2-17.

Rietveld-Van Wingerden. “Oorsprong van het Verhaal.” In De Schoone & het Beest. De Waare Rijkdom, Nr. 4. St. Geschiedenis Kinder- en Jeugdliteratuur. 2004. 11

Tatar, Maria. “Introduction: Beauty and the Beast.” In The Classic Fairy Tales: Texts, Criticism – Second Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017. 30-39.

Uther Hans-Jörg. The Types of International Folktales : A Classification and Bibliography : Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson: Pt. I, Animal Tales, Tales of Magic, Religious Tales, and Realistic Tales, Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia/Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2004.

Villeneuve, Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot. The Beauty and the Beast. New York: Harper Design, 2017.

Warner, Marina. “Cocteau’s Fairy Tale for Grown-ups.” In booklet to La Belle et la Bête. British Film Institute, 2018. 6-11.

Zipes, Jack. “Choosing the Right Mate: Why Beasts and Frogs Make for Ideal Husbands.” In The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films. New York: Routledge, 2011. 224-251.

Laat een reactie achter