Door Marc van Oostendorp

Whould there have been anything like Frisian without its literary authors? Would the language be taught in Frisian schools today? Would there be tv shows in Frisian? Would it be possible to use the language in court?

Whould there have been anything like Frisian without its literary authors? Would the language be taught in Frisian schools today? Would there be tv shows in Frisian? Would it be possible to use the language in court?

It probably is overly romantic to relate the fate of a language to the existence of a literary tradition. Isn’t speaking a language always more important than writing it? Isn’t a base of ordinary speakers worth more than a handful of poets? There might still be speakers if Frisian had never been written; there are a few hundred thousand of them now, mostly living in the province of Fryslân of the Netherlands.

Yet one can doubt that anybody would have felt the urgency to fight for the rights of this language if it would not have had the prestige that, arguably, initially came from the written tradition. Genetically, Frisian is said to be the Germanic language closest to English, but in the course of many centuries of intensive language contact, it has grown close enough to Dutch that a speaker of the latter language can follow Frisian with some effort. Still, it is probably very difficult to find any Dutch person who would deny that Frisian is a separate language. And the fight for its rights were definitely always stimulated by the existence of a literary tradition.

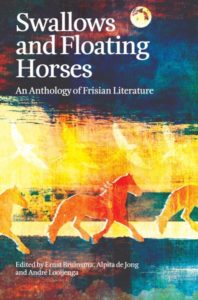

Swallows and Floating Horses is a sparkling and inspiring anthology of this tradition for an English-speaking audience. It offers original texts from the last 1,000 years and modern English translations. It features prose and poetry, texts from the Frisian heartland as well as from the more peripheral Frisian-speaking areas in Germany, and both from some of the more well-known authors as well as from some surprising names.

For this reason, the book is also enjoyable for readers who are already somewhat familiar with Frisian literature. One can for instance find the interesting lyrics of songs by Giacomo Vredeman (1558/9-1621), who had come to Frisia as a Protestant refugee from Flanders and who composed the music to texts that the editors call ‘saucy’:

Ick hab dy liaef mey al mijn hirt

By dy is al mijn nocht alline.

Mijn hymelrijck is ijn dijn schirt’,

En troch dijn aeghen schijnt mijn sinne.Eren do wy swylen, Lay ic mey ien int hae,

Te bortien en te lylen, Wy spylen pae om pae.

Jo woe so jern as ic, wy hien fen nimmen aân,

Wierom schoen wy’t naet dwaân.I love you, dear, with al my heart,

You are my only delight.

Your lap is most heavenly part

And through your eyes shines my sun’s light.Once we got the hay in, and with someone I lay.

We frolicked, kissed and kissed and sang while we were at play.

She was as keen as me, we saw no other men.

Why don’t we do it then?

Or a dadaist poem by Anne Feddema (1961-), written in honour of the German dadaist Kurt Schwitters, who visited Frisia in the 1920s on a dadaist tour (and himself wrote a poem containing some Frisian phrases):

Foar Kurt Schwitters

De buorman rint graach op

nullehakken!

De buorfrou rint graach yn in

baitsebokse!Baitseboksenullehakke!

Roppe se de diele dei.

En oarsom:

Nullehakkebaitsebokse!Mar juster, de skrik sloech my om it hert.

De buorfrou rûn op

nullehakken!

De buorman rûn yn in

baitsebokse!No rin ik de hiele dei op nullehakken!

Y in baitsebokse!Ik bin lokkich!

Ik rop:Nullehakkebaitseboksebaitseboksenullehakke!

For Kurt Schwitters

The man next door wears

stiletto heels!

The woman next door wears

chest waders!Chest-waders-stilettos!

They call the whole day long.

And the other way round:

Stilettos-chest-waders!But yesterday, I got the fright of my l life.

The woman next door was wearing

stiletto heels!

The man next door was wearing

chest waders!Now I walk around all day in stilettos!

Wearing chest-waders!I am happy!

I call:Stilettos-chest-waders-chest-waders-stilettos!

Obviously, the two giants of Frisian literature, Gysbert Japicx (1603-1666) and Tsjêbbe Hettinga (1949-2013), are also well-represented. Japicx was a schoolmaster who was brave enough to introduce the new Renaissance metrical forms in his mother tongue and excelled in it right away. These forms (like iambs) had just been introduced into the Netherlands a few decades earlier and arguably Standard Dutch was mostly created by the Dutch poets of the period – a period which has long been known in Dutch historiography as the ‘Golden Age’. Dutch was also dominant as a language of administration and of poetry in Frisia, but the work of Japicx convinced many that the written language had a quality that could match those of other emerging European languages. Since the emancipation movement of the 19th Century, Japicx has been seen as an iconic, maybe even mythological forefather. His qualities may have sometimes been a little exaggerated, but the three poems and the prose text in this anthology show that he was an interesting author indeed.

Ljeafke lit uwz sobbje’ in sabbje

t’Wijl ’t uwz muwlket, ljoent, in lest,

Dat iz immers fier’ wei best.

Litse gnorje’ in uwz belabbje,

Waems fjoer is oon yessche terd.

Alle dwaen het tijd in berd.Sinne in Moanne, rijzje’ in duwckje,

Simmer, Winter, Foar-jier, Hearst,

Fynje’ in libbje’ alweer az eerst.

Tuwttelke’, zaz w’uwz tijd naet bruwckje,

Nu-se’ uwz tjienet, jae rint t’ey,

Mar wa till’t weer holle’ oer-eyn.Darling, let us lip and lap,

While it gladdens, thrills and glees,

Nothing else can so wel please.

Some may grumble, tongues may flap,

But their fire will soon grow cold

For in time all things unfold.Sun and moon, they dive and climb.

Summer, autumn, winter, spring

Live and die, an endless ring.

Sweetling, do not tarry: time,

which serves us now, will soon have fled.

What dead man ever raised is head?

Tsjêbbe Hettinga was inspired by the work of Dylan Thomas – a poet of Welsh origin working in English. Hettinga took the original metrics of Thomas’ poetry and applied them to Frisian. The result of this was a type of poetry that became internationally known, for instance because it does not seem necessary to understand the precise meaning of what is being said in order to appreciate the poetry:

(Bekijk deze video op YouTube)

Frisian literature has always been a minority literature, and as such it has always undergone the influence of other literary traditions, without giving a lot back to those other literatures. Like many minority languages in Europe, Frisian is currently in a difficult position, although it is not really endangered yet. Swallows and Floating Horses shows the richness of human creativity – how even in a tiny corner of Europe people managed to express interesting thoughts and feelings in their own idiom – and created a language doing so.

Ernst Bruinsma, Alpita de Jong and André Looijenga (Eds.) Swallows and Floating Horses. An Anthology of Frisian Literature. London: Francis Boutle Publishers. Bestelinformatie bij de uitgever.

Wat in rykdom datst hjir ek oer skriuwst, en noch wol yn in wrâldtaal ek! Iksels bin fansels wol fan de Fryske literatuer oertsjûge, ek al bin ik dan gjin Fries, mar der kin altyd wol wat publyk by komme!