The dialogue as a literary genre has sunk into oblivion, but new forms of scripted spontaneous conversation (like podcasts) abide to the same rules as their medieval predecessors.

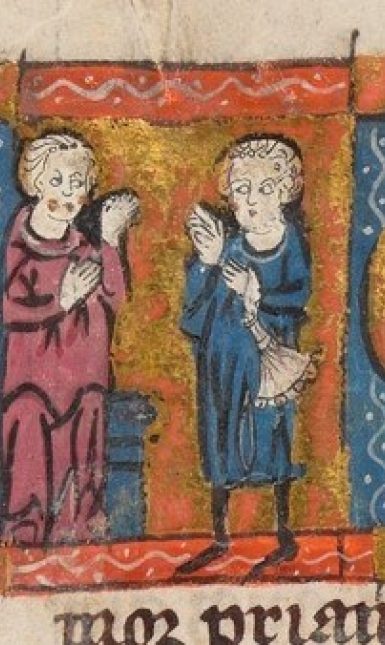

Two young men are engaged in lively conversation ever since an anonymous draughtsman portrayed them in the margins of a fifteenth-century (Dutch) treatise on the life of Christ (UBL Ltk 258). Five centuries later we still don’t know what they are they talking about.

We cannot hear their voices anymore. There are no speech scrolls, that could give us a clue. The men might be students that help each other understand the typological theology in the written words above their heads. But no effort has been made to link the image to the text, and the boys are not dressed like (tonsured) clerics. They are having a conversation of their own accord, informally, spontaneously and friendly, unlike the medieval standard images of conversation with masters instructing pupils or men and women in the delicate acts of courtly galanteries.

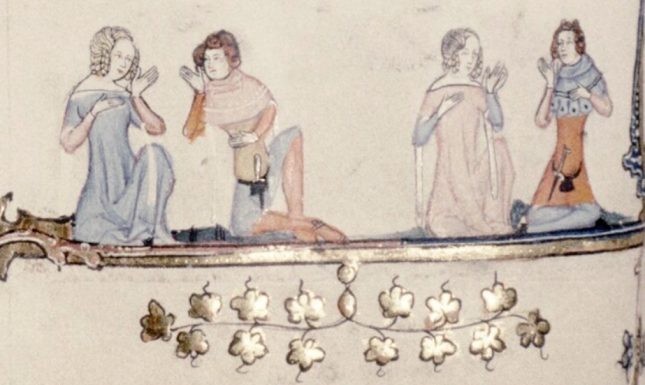

The dialogues represented in these images are easy to identify, as they reflect the literary culture of school education or epic romance and contemporary medieval conversational practice. The protagonists in these dialogues act in standard roles; the are usually not identified as individuals but rather as cleric, master, lovers, etc. The boys have most in common with an image of two poets in a jeu parti: contests between poets, mostly on amorous themes, that were more like a medieval rap battle than a conversation.

The boys in the Leiden manuscript, however, may just be chatting away, as individuals with personal interests, and apparently unaware of any third party, be it listeners or eavesdroppers.

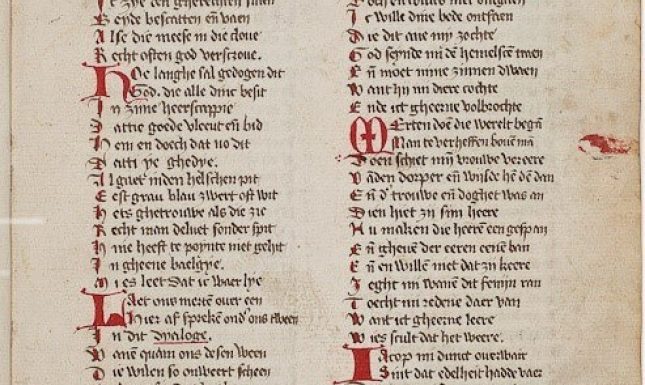

Taken as such, we might use the drawing to envision the (anticipated) performance of a particular set of Dutch dialogues of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century that were written by Jacob van Maerlant (available here) and his followers Jan de Weert and Jan van Boendale. They all introduce similar characters: two individuals that bear names like Jacob and Martijn, Jan and Wouter or Jan and Rogier. It cannot be a coincidence that in all dialogues one of the characters shares his first name with the author, but more important is that the participants interact as friends, instead of being portrayed in a role (like master and cleric). As a result, their conversations resist standard interpretations along the lines of authority and hierarchy that shape the disputatio (for which, see this article), which is the current medieval term for texts we would now label as dialogue. In fact, the Dutch word dialoghe is so rare that it was overlooked for the Middelnederlands Woordenboek (10 volumes!). The first conversation of Jacob and Martijn (by Jacob van Maerlant) seems to introduce the word dialoghe in Dutch, when the character Jacob invites his friend to discuss the miserable state of affairs at the courts:

Laet ons, Martijn, over een

Hier af spreken onder ons tween

In dit dialoghe

Together, Jacob and Martijn discuss the need for a change in government style. Jacob’s opening statement primarily expresses his own social discomfort:

Wapene, Martijn! hoe salt gaen?

Sal die werelt iet lange staen

In dus cranken love,

So moet vrouwe ver Ere saen,

Sonder twivel ende waen,

Rumen heren hove.

Ic sie den valscen wel ontfaen,

Die de heren connen dwaen

Ende plucken van den stove;

Ende ic sie den rechten slaen,

Beede bespotten ende vaen,

Alse die mese in die clove,

Recht offene God verscrove

[‘Beware Martijn! What will happen?

Will the world go on

in this miserable state (bad praise)?

Then Lady Honour will undoubtedly

leave the court of the lords soon.

I notice (literally: see) that the deceivers are welcome,

those that flatter the lords

and take their advantage.

And I notice that he that is just is being repressed,

mocked and put into prison,

like a bird in a trap,

as if God has turned him down’]

The cry for new leadership or bestuurscultuur is nothing new, but what now is being discussed in television talk shows openly (and endlessly), had to be put forward carefully and indirectly in thirteenth-century texts. Jacob suggests that he and Martijn speak among the two of them, implicitly emphasizing that no others are present or overhearing their conversation. Of course, this makes the dialogue a literary device to create a greater freedom of speech. The irony of pretending to have a private discussion in a scripted text to be read by (or performed in front of) a larger audience is easily recognizable and will surely not have been lost upon Maerlant’s contemporaries. But neither is it coincidence that Maerlant uses his dialogue for personal views, political opinions and the subjectivity of individual interests – that are largely absent in his larger encyclopaedic works on history, Bible and nature. The paradox of excluding bystanders in a dialogue is that it reduces the role of every reader to that of an eavesdropper, listening in on something that is – or was – not meant for her or him to hear.

As any public context is absent in these dialogues between friends, it has turned out problematic to (re)construct the original setting of Maerlant’s texts. They read like a script that could be performed by two boys like our friends in the Leiden manuscript. A fascinating hypothesis about Maerlant’s dialogues was inspired by another marginal drawing, of schoolboys with their master attending a puppet show.

The two puppets could indeed be used to bring to life dialogues like Maerlant’s, but the nature of his texts is intellectually too demanding for teenagers and puppetry. Even though the thirteenth-century image is much closer to Jacob and Martijn in time and place than the fifteenth-century friends in the Leiden manuscript, their attitude and gestures emphasize the exchange and interaction Maerlant expected in a dialogue:

eenen dyalogus,

Dats een bouc van II personen,

Die met goeden redenen ende sconen

Onderlinghe deelen haer wort,

Ende deen seget ende dander antwort.

The medieval Dutch is hard to translate accurately, but starting from the key notions one could read the following: ‘a dialogue is a written text (bouc means text and the materialized book) of two persons who exchange words with good and attractive discourse/arguments. One brings up an issue and the other responds’. This definition, the first of any literary genre in Dutch, comes from Maerlant’s last work (Spiegel historiael) and adequately lists the main components of a dialogue: a scripted version of a conversation between two people that is harmonious and sophisticated. This means for Maerlant dialogues served another purpose than the jeux partis of his days, that certainly needed an audience, whether fans or jury.

All in all, it is tempting to claim Maerlant invented something new, at least for Dutch literary culture. We could call it a prototype of the friendly and informal dialogues that would become one of the hallmarks of humanist culture (for which, see this book chapter). But there are other interesting parallels in modern media culture of podcasts, that explore the effects of settings that we have seen in Maerlant’s dialogues. Podcasts are recorded as if they were a private conversation between friends on current affairs or personal interests and anxieties, full of digressions and improvisation, without any awareness of bystanders or listeners. Of course, most of it is not true. Popular podcasts are produced to make money (through advertising), work with some sort of script (to ensure focus and coherence) and are very consciously created to entertain or inform an audience, even though listeners are supposed to experience the podcast as an overheard conversation. Especially, this last element puts listeners to a podcast in a position that is similar to that of dialogue readers. They are eavesdroppers, and therefore not immediately involved in the conversation – not even as live witnesses, side participants or bystanders. Just like Maerlant created a situation in which Jacob and Martijn could talk freely among the two of them, the two principle characters in the Dutch Zelfspodcast chat as if no one else is there. But read the Volkskrant article on the production of this podcast and be amazed about the ‘scriptedness’ of the whole enterprise.

Medieval dialogue and modern podcast share the paradox that personal experience is allowed as evidence in argumentation on matters of general interest. Participants are individual characters; their own circumstances and hang-ups play an important role in discussions on topics of a greater significance. The producers of the zelfspodcast even claim this personal touch is crucial for their ‘authenticity’ or credibility; much they share with their thirteenth-century predecessors Jacob and Martijn and their ghost writer Maerlant.

This blogpost originally appeared on the Leiden Medievalists Blog

Laat een reactie achter